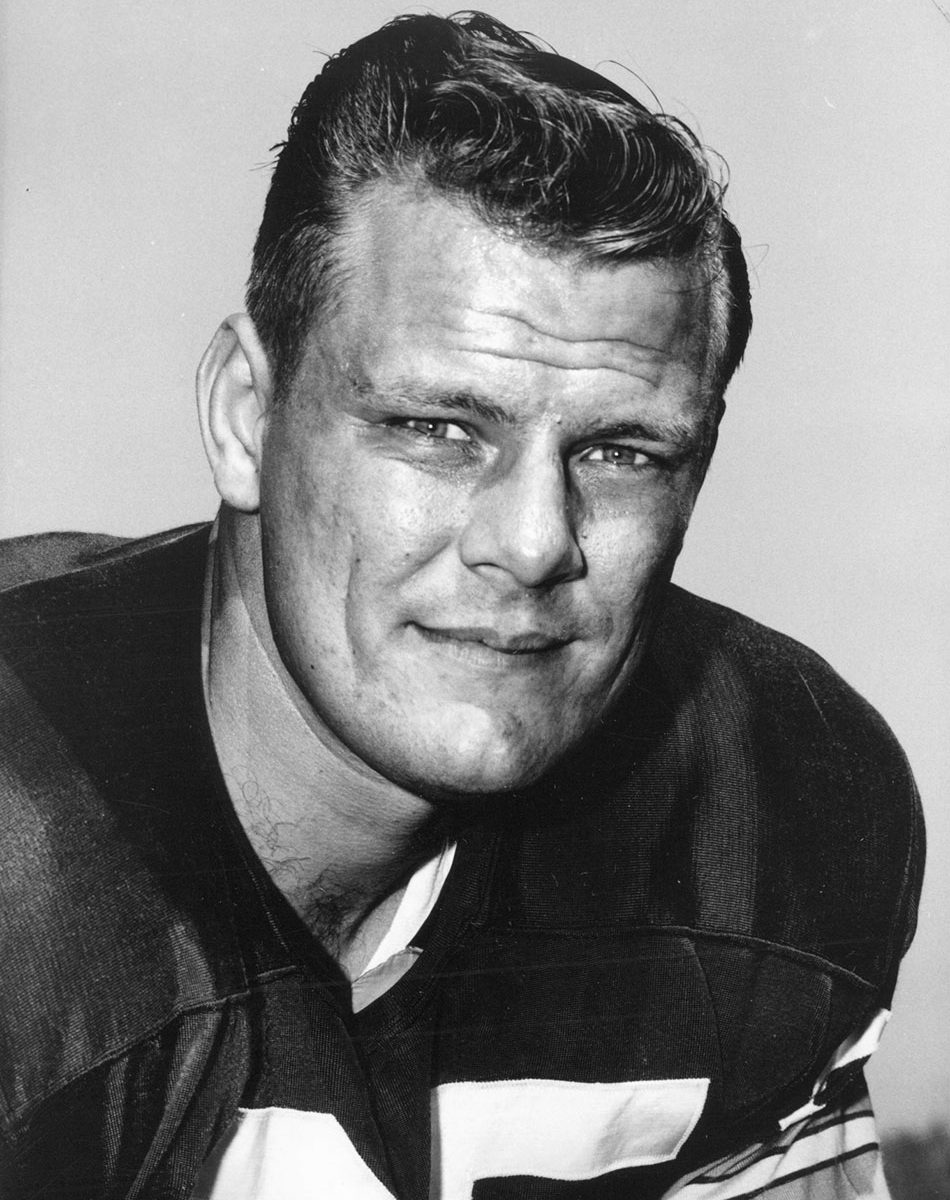

Born in Elmwood Park, Illinois, Nitschke was the youngest of three sons to Robert and Anna Nitschke. His father was killed in a car accident in 1940, and his mother died of a blood clot when Ray was 13. Older brothers Robert Jr. (age 21) and Richard (age 17) decided they would raise Ray on their own.

Nitschke entered Proviso High School in Maywood shortly before his mother’s death. The loss of both parents enraged Nitschke, and the lack of a parental disciplinarian to quell his rage caused him to engage in fights with other kids in the neighborhood. During his freshman year at Proviso, he played fullback on one of the school’s three football teams. He was a poor student and his grades eventually caught up with him as he was declared academically ineligible to play sports his sophomore year. He would lament this embarrassment for the rest of his life.

He succeeded in raising his grades sufficiently enough in his sophomore year to allow him to play sports his junior year, when he had grown significantly (to six feet tall). He starred on the varsity football team, playing quarterback on offense and safety on defense for coach Andy Puplis. He played varsity basketball and was a pitcher and left fielder for the varsity baseball team. His baseball skills brought him an offer from the professional St. Louis Browns with a $3,000 signing bonus. Nitschke was also offered scholarships from college football programs around the country. Puplis advised him to accept a football scholarship. Due to his desire to play at a Big Ten college, with a chance to play in the Rose Bowl, he accepted a football scholarship to the University of Illinois in 1954.

While attending the University of Illinois, Nitschke smoked, drank heavily, and fought at the drop of a hat. Never a good student in high school, his grades suffered at college. Similar to his contemporary, Jerry Kramer, Nitschke was ostracized by his professors because he attended the university as the result of a football scholarship.

In a game against Ohio State in the 1956 season Nitschke lost his four front teeth on the opening kick-off. Nitschke never wore a face mask and one of the Buckeye player’s helmets hit him in the mouth knocking out two teeth initially, the other two were hanging by the roots. He played the rest of the game.

In his sophomore year, due to a depletion of players in the offensive backfield, Illini head coach Ray Eliot moved Nitschke from quarterback to fullback, shattering his childhood dream of quarterbacking a team to a victory in the Rose Bowl. At this time, college football had reverted to primarily single-platoon football, meaning those players that were on offense had to switch to defense, and vice versa, when ball possession changed. On defense, Nitschke played linebacker. He proved to be a very skilled player and tackler as a linebacker, so much so that, by his senior year, Paul Brown considered him the best linebacker in college football.

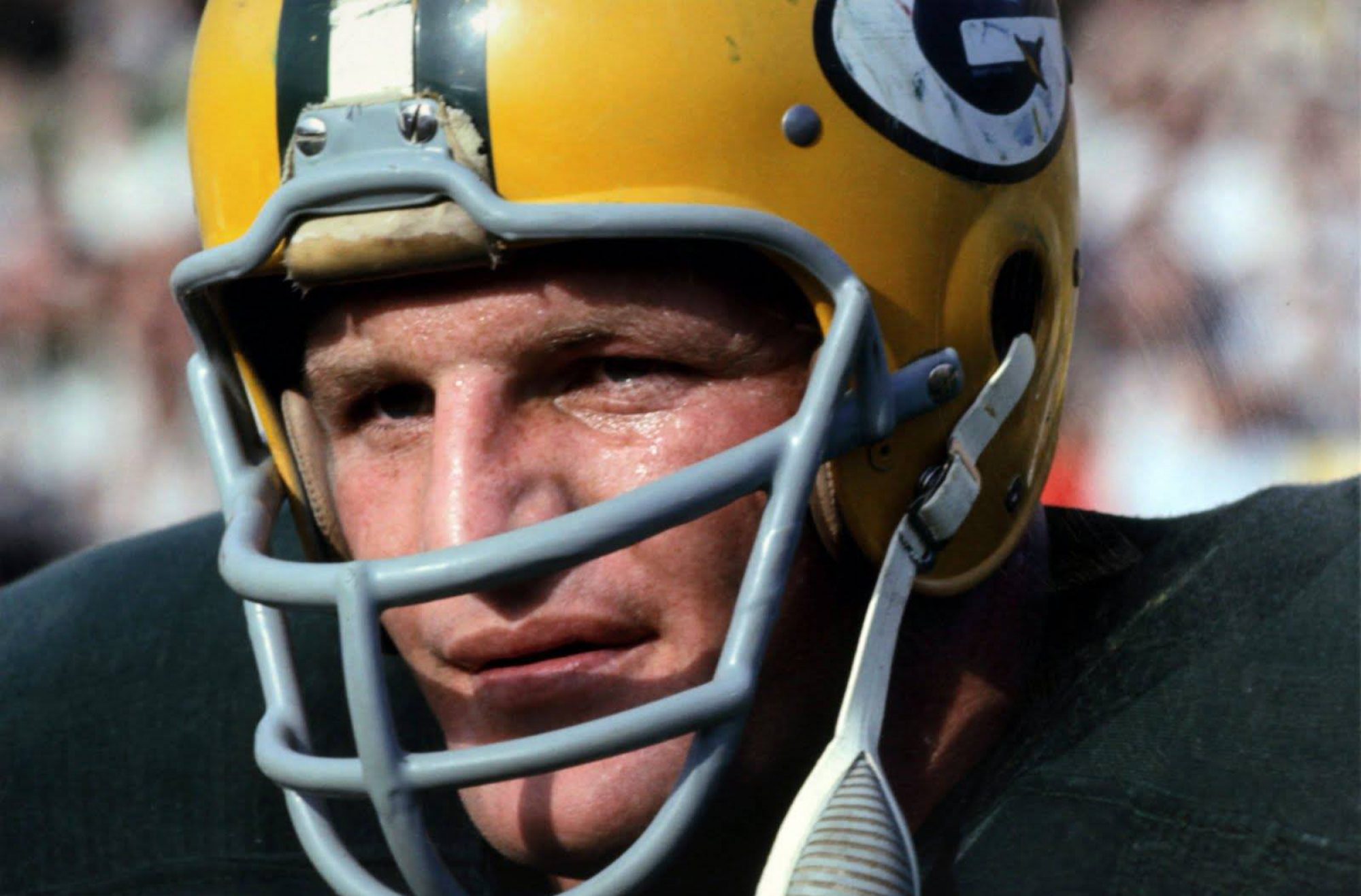

Growing up in the outskirts of Chicago, Nitschke had idolized the Bears and he hoped to be chosen by them in the 1958 NFL draft. However, on December 2, 1957, Nitschke was chosen by the Green Bay Packers as the second pick of the third round of the 1958 NFL Draft in what is considered the greatest drafting year in the history of the franchise. This draft included two other significant Packers of the 1960s, fullback Jim Taylor of LSU (2nd round, 15th overall) and right guard Jerry Kramer of Idaho (4th round 39th overall). Their rookie season in 1958 was dismal as the Packers with just one win and one tie finished with the worst record in the 12-team league. Nitschke wore number 66 his entire career with the Packers.

A month after the 1958 season ended, Vince Lombardi was hired as head coach. Nitschke became a full-time starter in 1962, the anchor of a disciplined defense that helped win five NFL titles and the first two Super Bowls in the 1960s. He was the MVP of the 1962 NFL Championship Game, accepting the prize of a 1963 Chevrolet Corvette. In the game, Nitschke recovered two fumbles and deflected a pass that was intercepted. The Packers won, 16-7, and finished the season with a 14-1 record. In Super Bowl I, Nitschke contributed six tackles and a sack. In Super Bowl II, Nitschke led Green Bay’s defense with nine tackles.

On December 17, 1972, the 9-4 Packers traveled to New Orleans to play the 1-11-1 Saints at Tulane Stadium for Nitschke’s last regular-season game of his career. Nitschke recorded the only pass reception of his career in this game, a 34-yard gain after a blocked field goal attempt for which he was blocking, and the Packers won the game, 30-20. they had clinched the NFC Central division title the week before, their first playoff berth since Super Bowl II. Green Bay lost on the road to the Washington Redskins, 16-3, in the first round of the playoffs. Nitschke retired during the following year’s training camp, in late August 1973.

Nitschke was known for his strength and toughness. On Sept. 1st, 1960, a steel coaching tower on the Packers practice field was blown over by a strong gust of wind on top of Nitschke. Lombardi ran over to see what had happened, but when told it had fallen on Nitschke, said, “He’ll be fine. Get back to work!” According to Nitschke’s biography, a spike was driven into his helmet, but did not injure him. The helmet (with the hole) is currently on display in the Packer Hall of Fame in Green Bay. Although Nitschke was known for his hard hitting, he was an athletic all-around linebacker who also intercepted 25 passes over his career.