Boxing

Boxing

Does boxing need to be saved?

The popular notion that boxing needs to be saved is ludicrous. It brings to mind the old joke about how boxing has been buried so many times they’ve run out of shovels.

There will be 90,000 fans at Wembley Stadium to see Anthony Joshua fight Wladimir Klitschko on Saturday, and the only thing that might need saving is one of the fighters.

As soon as the match was made, there was excited chatter about how Joshua might become boxing’s next savior, providing, of course, he beats Klitschko in a definitive manner. We have, of course, been down that road before with decidedly mixed results. There are no sure things in boxing.

Nonetheless, wishful thinking is part of the fun, which shouldn’t be surprising in a sport populated with dreamers. Fans and, to some degree, the industry itself often crave a savior to pull it out of doldrums. It has been a reoccurring theme throughout boxing history. But beware of false prophets. They’ll break your heart every time.

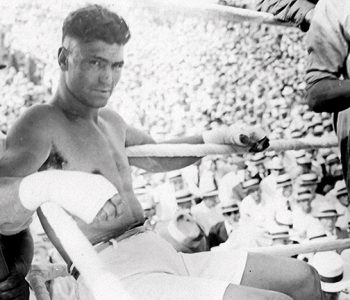

One of the best examples was Jess Willard who flattened Jack Johnson in 1915, ending the reign of boxing’s first black heavyweight champion, much to the relief of the Caucasian establishment. To its way of thinking, the 6-foot-6 “Pottawatomie Giant” had saved boxing

Willard, however, didn’t really enjoy fighting. The former Kansas cowboy only fought because it was the best way he knew to make money. As champion, he cashed in on the exhibitions circuit but made only one successful defense during the four years he held the title, hardly a schedule conducive to saving the sport.

Jack Dempsey, who brutalized Willard to take the heavyweight championship in 1919, came closer to the mark. He was boxing’s biggest attraction during America’s Golden Age of Sports, an exhilarating time, teeming with iconic sporting heroes such as Babe Ruth, Red Grange, Bill Tilden and the first equine superstar, Man o’ War.

The “Manassa Mauler” wasn’t worried about saving boxing. He had the raw aggression and crippling punching power that people paid to see, plus wily manager Doc Kearns in his corner. Together they took boxing to the next level when Dempsey’s knockout of Georges Carpentier in 1921 generated boxing’s first million-dollar gate.

Willard and Dempsey were at opposite ends of the savior spectrum, one a flop the other a sensation, but typical of a process where many are called but few are chosen.

Savior probably isn’t the best word to describe the phenomenon under discussion. Lodestars would be more accurate. There’s nothing miraculous about it. It’s simply a product of the cyclical natural of all things, including boxing.

An exceptional fighter doesn’t swoop to the rescue like the cavalry in a John Ford western. Relief comes when a superior boxer appears naturally. The trick is figuring out who’s for real and who’s not.

Joe Louis was as real as it gets, a game-changer, the first black boxer to knock the wind out of Jim Crow and the only heavyweight champion to make 25 successful title defenses. Managers Julian Black and John Roxborough knew he was special from the get-go, and it didn’t take long for the rest of the world to catch on.

Muhammad Ali dragged the sport back into the light after the long, dark winter that followed the televised death of Benny “Kid” Paret. He was a great fighter, a revolutionary and a beacon of hope to the downtrodden. But boxing didn’t stop when he did.

Countless Ali imitators came in his wake, false prophets one and all. And when the next superstar arrived it was a baby-faced welterweight with a gold medal around his neck by the name of Sugar Ray Leonard.

The heavyweights never had a monopoly on excitement. Leonard was the catalyst for a thrilling series of superfights in the late 1970s and early ’80s. His bouts with Roberto Duran, Thomas Hearns and Marvin Hagler created an atmosphere in which other future Hall of Famers such as Aaron Pryor, Salvador Sanchez and Wilfredo Gomez could thrive. The memorable epoch was a group effort, not a one-man show.

There was no shortage of Leonard wannabes. Terry Norris (who beat a badly faded Leonard) and Donald Curry were the best of those optimistically referred to as the “next Sugar Ray Leonard.” But there was no “next” Sugar Ray Leonard. He was the closest thing to the original Sugar Ray (Robinson) boxing is ever likely to see.

The irregular cycle of brilliance continued with Mike Tyson, Julio Cesar Chavez, Oscar De La Hoya, Floyd Mayweather Jr., Manny Pacquiao and others. It’s an ongoing organic process that creates a chain of greatness in which the purported saviors are but links.

Those heavyweights who promised much but delivered little, such as Gerry Cooney, Michael Grant and Samuel Peters, are reminders of the danger involved in rushing to judgment, especially in a business where one punch can change everything.

There is also a geographical element to the rise and fall of boxing’s popularity. Like politics, all boxing is local. The area might be as big as a continent or as small as a neighborhood, but local all the same. Andre Ward is among today’s finest boxers but only draws well in his hometown of Oakland. It’s the same with Terrence Crawford and Omaha.

Conversely, when Pacquiao was in his pomp, the entire Filipino diaspora turned out whenever he fought outside the Philippines, where daily life came to a halt while the nation watched as one. But don’t forget that, until he entered the ring at the MGM Grand as a late sub and obliterated Lehlo Ledwaba, very few considered Pacquiao destined for greatness. Sometimes a lodestar appears seemingly out of nowhere.

Mayweather created an identity that made him one of the richest athletes in the world by combining mind-blowing skills and masterful marketing. Even though he hasn’t boxed since September 2015, the sport refuses to cut the umbilical cord, dangling a possibility of a fight with MMA star Conor McGregor as click bait in a frantic bid to stay relevant.

Ultimately, it’s a losing strategy. Mayweather might fight again or he might not, but either way, boxing has to move on and trust in the sport’s innate ability to reinvent itself.

Moreover, the disaster that is Adrien Broner should be ample warning of the perils of attempting to duplicate Mayweather’s unique success.

If you asked U.K. fans whether boxing needs saving, the most likely answer would be, “What the hell are you talking about? It’s never been better.” And therein lies one of the truths beneath the myth of the sport’s saviors: Boxing is an international sport, and a good time in one part of the globe doesn’t necessarily mean good times everywhere. Which brings us back to Joshua and Klitschko.

Should the 41-year-old ex-champ regain the title, the heavyweight scene will be much the same as it was before Tyson Fury outfoxed Klitschko and won the title in 2015. A lucrative victory lap of European venues against nondescript challengers would surely follow a Klitschko victory.

Joshua is a different story. He’s already a crossover star in the U.K and has been since winning the super heavyweight gold medal at the 2012 Olympics Games in London. If he thrashes Klitschko, his popularity at home will know no bounds.

How that would translate in America is difficult to know. England’s Lennox Lewis never totally won the hearts of U.S. fans but gradually earned respect as one challenger after another toppled at his feet.

At this stage of Joshua’s career, it would be premature to compare him to Lewis. Even so, he has an aggressive approach and a concussive right hand, a winning combination that never goes out of style. A showdown with Deontay Wilder could conceivably be the biggest heavyweight title fight in the U.S. since Lewis knock out Tyson in 2002.

But don’t get me wrong. The winner wouldn’t be the savior of boxing because boxing doesn’t need saving. It is, however, ready for another spike in its vacillating progression through time and space.

If Joshua isn’t the one destined to return excitement to the heavyweight division, somebody will come along eventually. They always do.

SOURCE: ESPN

by: Nigel Collins | ESPN Staff Writer